Microbenchmarking fused instruction.

04 Feb 2018

Contents:

Subscribe to my newsletter, support me on Patreon or by PayPal donation.

Let me start this post with a question: “Do you think number of executed(retired) instructions is a good metric for measuring performance of your application?”.

Well, it is a decent proxy, but not an one-to-one match to the timings of the benchmark. And in this post I will show when it can be the case.

My story

One day I was dealing with performance degradation in some benchmark. I immediately spotted lots of differences in assembly code between “good” and “bad” cases. For the same C++ source code:

// for loop with induction variable i and array a

a[i]++;

for “good” case there was an assembly like the following:

inc DWORD [<memory address>]

and for “bad” case there was assembly like that:

mov edx, DWORD [<memory address>]

inc edx

mov DWORD [<memory address>], edx

So, in the latter snippet it’s basically the same instruction but split in 3 simpler instructions.

Performance delta was not that big: around 5%. I checked profiles - no other significant difference, besides… Number of instructions retired in “good” case was ~50% lower than in the “bad” case. Similar patterns can be observed in many different places in the hot path of the benchmark. At that point I considered: “problem solved, there is no sense in splitting instructuions like that”. Or rather say, not fusing them. I thought that some pass in the code generation phase failed at combining 3 simple instructions into a fused one.

I revisited that case after a few days when my colleague pointed out to me that this shoudn’t be the source of the problem. I did more experiments just to find out that it was yet another code alignment problem (check out my recent post on this topic). With adding one of the code alignment options to the compilation yielded the same performance for both cases.

Fusion features in x86

If we look closer at the fused instruction it actually consists of a three operations: load from memory, increments the value and store it back. There is no magic here, CPU will execute those operations either way.

Before I present the benchmark I want to say a few words about fusion features that exist in Intel Architecture Front End starting from “Sandy Bridge”. Execution engine (back-end) inside the cpu can only execute so-called “micro-ops” (uops), that were provided by the front-end. So, back-end can’t execute fused instruction but only a simple ones. There are some limitations to which operations can be fused and which not, more about this feature you can read in Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Optimization Reference Manual, section “2.4.2.1 Legacy Decode Pipeline”.

Please do not be confused about the difference between InstructionFusion, MicroFusion and MacroFusion. According Intel documentation:

- InstructionFusion is when multiple RISC-like assembly instructions are merged into CISC-like one assembly instruction (see example above). This is made by the compiler / asm developer.

- MicroFusion is when multiple uops from the same assembly instruction are merged into one uop. This is made by the decoding pipeline inside CPU.

- MacroFusion is when multiple uops from different assembly instructions are merged into one uop. This is made by the decoding pipeline inside CPU.

Benchmark

I decided to use uarch-bench for my experiments as it allows quite precise collection of performance counters for the snippet of assembly you provide.

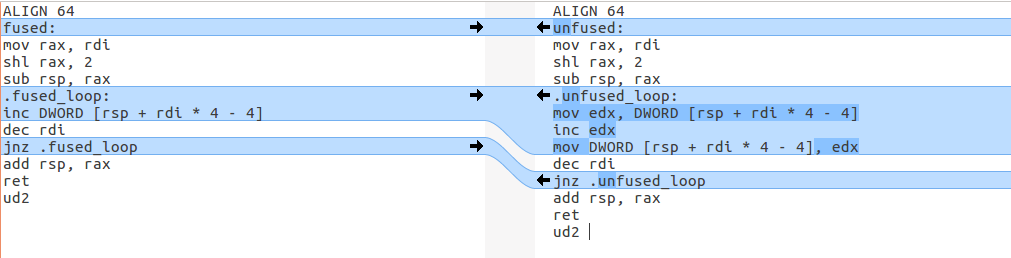

Here is the difference in assembly for the two benchmarks I ran:

Those two assembly functions (

Those two assembly functions (fused and unfused) take number of iterations as an argument (that ends up in rdi, see x86 calling conventions). Also they allocate integer array on the stack with the number of elements equal to the number of iterations. In the nutshell this assembly code is equivalent to this C code (number of iterations = 1024):

void fused(/*int iters = 1024*/)

{

int a[1024];

for (int i = 0; i < 1024; ++i)

{

a[i]++;

}

}

I ran two benchmarks on my home Intel Core i3-3220T (Ivy bridge). I expect to see similar results on more modern architectures like Haswell and Skylake.

Here are the results I received:

| Benchmark | Cycles | INSTRUCTIONS_RETIRED | UOPS_ISSUED | UOPS_RETIRED | LSD.UOPS |

|-----------|--------|----------------------|-------------|--------------|----------|

| fused | 2.32 | 3.05 | 5.36 | 5.36 | 4.80 |

| unfused | 2.32 | 5.05 | 5.36 | 5.36 | 4.88 |

“Cycles” shows how many cycles were executed per one loop iteration. So, essentially, harness calls the function, measures performance counter that you requested and then devides it by the number of iterations.

If we do the calculation for INSTRUCTIONS_RETIRED:

- fused:

INSTRUCTIONS_RETIRED = 3 (function header) + 1024 * 3 (loop) + 2 (function footer) / 1024 = 3.005 - unfused:

INSTRUCTIONS_RETIRED = 3 (function header) + 1024 * 5 (loop) + 2 (function footer) / 1024 = 5.005

We can also see that measurement overhead is (3.05 - 3.005) * 1024 = ~46 instructions.

But if we look at UOPS_ISSUED metric we will see that they are equal. That leads us to the thought that the fused instruction was split inside the decoder into 3 smaller uops. And after that there is no impact on the execution engine, so we have a strong proof why performance of those two cases is on par.

One more interesting thing I want to mention is that both of those 2 loops run almost fully out of LSD. In both cases LSD.UOPS is very close to UOPS_ISSUED meaning that LSD recognized the loop after some number of iterations. After that it started feeding back-end with already fetched and decoded uops. But it takes some time for LSD to detect the loop that’s why this number is slightly lower than the total number of issued uops. More information about LSD can be found in Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Optimization Reference Manual, section “2.4.2.4 Micro-op Queue and the Loop Stream Detector (LSD)”.

Conclusion

Intel Optimization Manual (that I mentioned several times already) says the following:

Coding an instruction sequence by using single-uop instructions will increases the code size, which can decrease fetch bandwidth from the legacy pipeline.

Out of all runs that I did unfused version was never faster then the fused one.

Encoding of fused instructions in my example takes 4 bytes, when unfused version takes 10 bytes. Significant win. It also involves different alignment of the code that goes after that instruction which potentially can make a difference in performance going up or down.

I was also trying to expose the gain from better utilization of fetch bandwidth, but looks like it’s not so straightforward. I tried manually unrolling the loop and doing other sort of things, but as what I understand in my toy examples latency of the memory operations (even though data should be in the L1-cache) are big enough to hide the inefficiencies in fetch and decode bandwidth. According to Agner Fog’s instruction tables fused load-op-store operation takes 6 cycles. If anyone will have a good example where fused version is significantly faster - please share it with me.

Another interesting thing which can cause difference in performance for the cases mentioned in the post is connected with decoders. From the Intel Optimization Manual:

There are four decoding units that decode instruction into micro-ops. The first can decode all IA-32 and Intel 64 instructions up to four micro-ops in size. The remaining three decoding units handle single-micro-op instructions. All four decoding units support the common cases of single micro-op flows including micro-fusion and macro-fusion.

However, I haven’t tried to write a microbenchmark for that.

Unfused instructions also add register pressure to the compiler, because it needs to find the free register to load the value from the memory.

UPD 05.02.2018:

I found that in the comments that there were lots of confusion in terminology between Instruction fusion, MicroFusion and MacroFusion.

I tried to use the same terminology as in Intel documentation. Please see updated “Fusion features in x86” chapter.

UPD 09.02.2018:

Title of the post was changed. I used it by a mistake and it caused a lot of confusion.

All content on Easyperf blog is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License